It's a fair and a good question. If you put something in print and work through the process of communicating, refining, and sometimes defending ideas, trying to get others to read and understand and possibly agree with you, you probably have some deep-seated reason that drives you to write. That reason for writing probably lies somewhere close to the author's heart. It's part of her or his outlook, a glimpse into their inner workings. And many readers want such a glimpse. They want to make contact not just with the ideas but with the person and motivation behind the ideas. At bottom, I think a lot of people are fairly ad hominem in our reading, especially of polemics.

I've searched for a good answer to the question, "Why did you write The Decline of African American Theology?" I wandered through a a handful of answers, all of them true but none of them quite right.

Tonight I watched an episode of Bill Moyers Journal, a PBS program that sometimes focuses on religious themes and ideas. It was an interview with African-American theologian, professor and author Dr. James H. Cone of Union Theological. Dr. Cone is the author of a number of books very influential among African-American academics and religious thinkers. He is the father of the Black Theology movement, an attempt to do theology with a liberationist ethic from the distinct vantage point of African American experience.

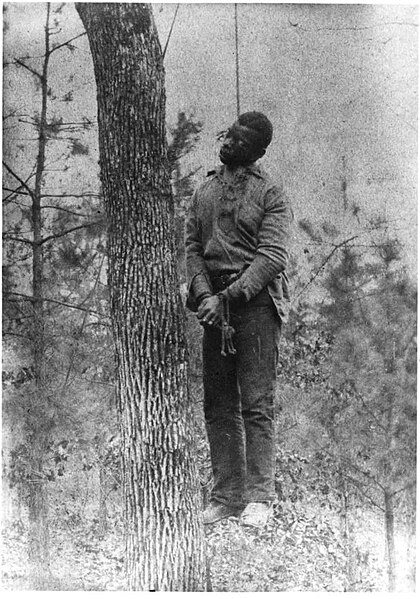

Tonight I watched an episode of Bill Moyers Journal, a PBS program that sometimes focuses on religious themes and ideas. It was an interview with African-American theologian, professor and author Dr. James H. Cone of Union Theological. Dr. Cone is the author of a number of books very influential among African-American academics and religious thinkers. He is the father of the Black Theology movement, an attempt to do theology with a liberationist ethic from the distinct vantage point of African American experience.The Moyers interview was prompted by a 2006 lecture that Dr. Cone delivered at Harvard (watch). The lecture used American lynching as a metaphor for understanding the cross of Christ. The entire interview is worth watching if you're inclined. You'll see into the heart and thinking of perhaps the most influential African-American theologian in the last 50 years.

There is much that could be said about the interview. But rather than comment at length, pasted below are two brief exchanges between Mr. Moyers and Dr. Cone. I copy the comments because they finally helped me to say briefly what my motivation was for writing The Decline.

BILL MOYERS: And you say, "The cross and the lynching tree interpret each other. Both were public spectacles usually reserved for hardened criminals, rebellious slaves, rebels against the Roman state and falsely accused militant blacks who were often called black beasts and monsters in human form." So, how do the cross and the lynching tree interpret each other?

BILL MOYERS: And you say, "The cross and the lynching tree interpret each other. Both were public spectacles usually reserved for hardened criminals, rebellious slaves, rebels against the Roman state and falsely accused militant blacks who were often called black beasts and monsters in human form." So, how do the cross and the lynching tree interpret each other?JAMES CONE: It keeps the lynchers from having the last word. The lynching tree interprets the cross. It keeps the cross out of the hands of those who are dominant. Nobody who is lynching anybody can understand the cross. That's why it's so important to place the cross and the lynching tree together. Because the cross, or the crucifixion was analogous to a first century lynching. In fact, biblical scholars-- when they want to describe what was happening to Jesus, many of them said, "It was a lynching."

While I don't want to press it too far, I do think there are some interesting parallels between lynching and the cross that can help us better understand the gospel. But what God and the Cross are reduced to in this interview is appalling. No biblically recognizable cross and no glory.And all I want to suggest is if American Christians say -- they want to identify with that cross, they have to see the cross as a lynching. Any time your empathy, your solidarity is with the little people, you're with the cross. If you identify with the lynchers, then, no, you can't understand what's happening. That in the sense of resistance-- what resistance means by helpless people. Power in the powerless is not something that we are accustomed to listening to and understanding. It's not a part of our historical experi-- America always wants to think it's gonna win everything. Well, black people have a history in which we didn't win. We did not win. See, our resistance is a resistance against the odds. That's why we can understand the cross.

**************

BILL MOYERS: Do you believe God is love?

JAMES CONE: Yes, I believe God is love.

BILL MOYERS: I would have a hard time believing God is love if I were a black man. I mean, those bodies swinging on the tree. What was God?Where was God during the 400 years of slavery?

JAMES CONE: See, you are looking at it from the perspective of those who win. You have to see it from the - perspective of those who have no power. In fact, God is love because it's that power in your life that lets you know you can resist the definitions that other people are being-- placing on you. And you sort of say, sure, nobody knows the trouble I've seen. Nobody knows my sorrow. Sure, there is slavery. Sure, there is lynching, segregation.But, glory, hallelujah. Now, that glory hallelujah is the fact that there is a humanity and a spirit that nobody can kill. And as long as you know that, you will resist. That was the power of the civil rights movement. That was the power of those who kept marching even though the odds are against you. How do you keep going when you don't have the battle tanks, when you don't have the guns? When you don't have the military power? When you have nothing? How do you keep going? How do you know that you are a human being? You know because there's a power that transcends all of that.

BILL MOYERS: So, how does love fit into that? What do you mean when you say God is love?

JAMES CONE: God is that power. That power that enables you to resist. You love that! You love the power that empowers you even in a situation in which you have no political power. The-- you have to love God. Now, what is trouble is loving white people. Now, that's tough. It's not God we having trouble loving. Now, loving white people. Now, that's-- that's difficult. But, King -- you know, King helped us on that. But, that is a-- that is an agonizing response.

The Decline of African-American Theology is a jeremiad, a long lament over a deep fall. Some will lament the decline, and others will lament The Decline. Of that I'm sure.

But after listening to Moyers and Cone tonight, I realized that I wrote the book because I am deeply sad. I'm sad about the state of the church in African American communities, and the very real eclipse of the gospel where African Americans gather and worship. And I'm sad because I love the Lord, His gospel, His people, and the nations who need the Lord, His gospel, and His people. The book isn't sad, I don't think, but its author is.

To be sure, my motives are alloyed with pride and some other things that need the sanctifying grace of Christ. But at bottom, I grieve that "my people perish for lack of knowledge" of the gospel of Jesus Christ. I pray this little book may be used by the Lord in the hands of good and faithful saints to turn the mourning of many into laughter.

18 comments:

Brother, I join you in the mourning, as we labor for morning to come. Do know that you have a friend, a brother, and a comrade in me. Keep up the struggle!

This is an excellent and thoughtful post, Thabiti. I look forward to reading the book. I pray your labors accomplish much for the eternal Kingdom. May the Lord use the book gloriously for His purposes.

I praise God for you and this book! What a joy to hear the rumblings of reformation in the African-American community... Come, Lord Jesus!

Thank you for this post brother. My heart resonates with yours and I share your sadness. I have to say that my emotions on this topic regularly range between sadness, anger, discouragement, and hope.

I've ordered two copies of the book, one for me and one for my former pastor. I figure that would be more honorable than waiting for Twin Lakes Fellowship and hoping to get a free copy!

May we see, yet again, God using the weak things of the world to demonstrate His glory!

Thanks for sharing your heart with us. I pray that God will grant us all 20/20 Gospel vision, in that we can see the nations, and we can see our own and cry out for God to save souls.

What an honour it is to have spent some time with you and to be able to say I know you in a small way. Thank you for this post. You have just told me here why I will be telling my wife to buy me this book for Christmas.

bless you brother,

I will be getting my copy soon.

Q

Thabiti,

You are being attacked pretty harshly at Between Two Worlds blog in the comment box, regarding your book. Please respond.

Hi Anonymous #2,

Thanks for visiting the blog and taking interest in this important discussion. I won't answer on Justin's blog; I don't want to hijack his post.

Neither do I wish to defend myself personally. Honestly, I'm worthy of blame for far more egregious things than are said at JT's blog--far more egregious. I'm a sinner that deserves hell. But God in Christ has treated me better than my sins deserve.

But here are a couple things I think folks should consider who engage in critical reflection on ideas (whether my book or any other):

1. Pray for the church. Whatever our position on these things, the most active way to be involved is to call down heaven for the kingdom of God to come on earth as it is in heaven and for the Lord's will to be done on earth as it is in heaven.

2. We shouldn't resort to ad hominem arguments. Engage the ideas. Evaluate them on their own merits. Consider the evidence--and counter-evidence--and reach an informed conclusion. Don't dismiss the ideas by attacking the person. That is a fallacious approach to debate and logic.

3. We should resist the idea that if you're not in my group (ie, inside the African American church) then there is nothing you can say about the church that's profitable. That's a very widespread sentiment, that effectively means we're not open to learning from others. It divides the body of Christ in a way that Christ never does... along ethnic and, perhaps in this case, ideological lines. It may be that pride gets the better of us when we approach dialogue/debate this way, and we miss the grace of God available to us in the teaching and wisdom of others. Who would say to Don Carson, for example, don't write a book on the emergent church since you're not a member of one? Or who would say to James Cone, for that matter, don't critique the prosperity preacher and their churches since you're not a member there? We wouldn't, if we're teachable and thirsting after knowledge. We'd evaluate what they say and cling to the truth we find.

3. Perhaps this should be the first point, but we should actually read the work before we critique it. Perhaps these persons have; I don't know. But when we engage others on issues of this sort, we should at least be familiar with their argument. And, as mentioned in point 1, respond to the argument itself.

4. Pray some more.

A few posts earlier on Justin's blog, he mentioned Roger Nicole's excellent piece on how to disagree with others. That would be well worth the reading.

Hope this helps.

Thabiti

Can't wait to read this book. Thanks for holding it down Pastor- In Christ

Brother Thabiti,

I’m not here to add to any misunderstanding. I am seeking to make sense of the situation and hopefully with your help and clarification. I think understand your rebuttal in #3 (above) when you said, “We should resist the idea that if you're not in my group (ie, inside the African American church) then there is nothing you can say about the church that's profitable…Who would say to Don Carson, for example, don't write a book on the emergent church since you're not a member of one? Or who would say to James Cone, for that matter, don't critique the prosperity preacher and their churches since you're not a member there? We wouldn't, if we're teachable and thirsting after knowledge. We'd evaluate what they say and cling to the truth we find.” However, I do not think being teachable or clinging to truth is necessarily the main thrust behind the critique of you and your book. It seems like to me the issue is not so much whether different groups are or should be teachable, but rather whether certain people (i.e., critics) who are outside of those groups are actually credible, especially if they do not at least know well and take serious the people and their experiences they say needs their teaching or correction in most cases.

I say this because I do not see your Carson or Cone example as being analogous to your situation. Both Carson and Cone are a part of – internal – to that which they are both critiquing. In other words, neither Cone nor Carson stand outside of the institutions they are critiquing. Carson is a part of the wider white evangelical church that includes some of the emerging church; Cone is a part of the Black church that includes some prosperity teaching. Given those circumstances, that gives Cone and Carson a good measure of credibility to speak into and critique the institutions that they themselves are a part of. As far as I can tell, we have seen both Cone’s and Carson’s love for the institutions/people they are critiquing, not just because they told us so, but because they have demonstrated their love by giving of their lives while still living among and being a part of the very same people whom they may be at odds.

Of course, there may be some "truth" to what outsiders may say about any given community, but that does not mean they (i.e., the outsider) should carry any authorial/judicial weight just because they are talking about what they think is right or wrong about a certain community. Therefore, the idea of being teachable has everything to do with the credibility of the critic based upon any given community’s internal standards of credibility. In general, why should anyone listen to someone critiques/teaching when their (the critic’s) love for them has not been historically evident in any kind of meaningful way?

Thabiti,

In light of the fact that you have diagnosed the problem of the decline of African American Theology, can you share with us your solution to this problem? How do we turn this around? There is a growing number of individuals who recognize this problem that is the center of your book. But what are you recommending?

Hi Xavier,

Welcome to the chat brother.

The critique trades in identity politics. It assumes, to use your words, that "credibility" is "established" by a certain kind of affiliation. It also assumes--wrongly, I might add--that in this case I'm outside the "black church" and therefore without "credibility" to speak on the issue.

As for the examples, neither Cone nor Carson have "credibility" because they're in the wider circle of the perceived "in group." What gives them credibility is the accuracy of their critique and their understanding of the subjects. It wouldn't matter to any of us if Carson wrote a book on the emerging church or even the E-Free churches (choosing a circle he very much is in) if, in fact, the book was demonstrably sloppy and weak in its sources, reasoning, etc. He wouldn't be credible just because he's in the group. That's akin to saying someone can speak for the black community because they're black. We'd all reject that. And we need to resist all such forms of identity and philosophical hegemony.

Brother, the "weight" or "authority" any comment has lies in whether or not it's true. To be sure, we're to speak the truth in love. But it is the truth--especially the truth of God's word--which is to command our attention, response, and gratitude. And if we're teachable, we don't despise the truth because of the bearer. We don't shoot the messenger. we mine the message for whatever gold is there. We chew fish and spit out the bones as the bros in the islands would put it.

Brother, I assume from a couple of your comments that you're impugning my love for the African American church. At that, all I can say is you really don't know me at all. You don't know my history or my present. Reading that Roger Nicole article would be well worth the investment.

With sincere love for you and all the brothers of our hue,

Thabiti

Anonymous,

You wrote: "In light of the fact that you have diagnosed the problem of the decline of African American Theology, can you share with us your solution to this problem? How do we turn this around? There is a growing number of individuals who recognize this problem that is the center of your book. But what are you recommending?"

Thanks for your question. It's the appropriate one. And any constructive project in the church--whatever the theological or philosophical orientation--must grapple with it.

The Afterword in the book gives a very summary outline for some steps forward. I hope to give attention to this in a future work, should the Lord give me life and grace.

T-

Thabiti,

I’m not attacking your person, bro. So please don’t take this personal. I think you are a beautiful Black brother whom I appreciate. But we must be careful not to give way to and allow for the possibility of short circuiting the conversation that we must have as Black (Reformed) brothers by assuming that someone who provides a critique does not have one’s care or best interest in mine. Forbearance on ideological/theological matters among Blacks can only materialize if we have genuine love for each other.

My comments were not character assessments, but intellectual assessments of one’s ideological/theological arguments. To be sure, I am not questioning your love for Black communities, but we also have to be honest and admit that just because somebody is Black does not mean that their “love” for the Black communities is above critique. That is the beautiful history of Black intellectual/religious discourse.

Communal Love + Communal honesty + Communal Intellectual Discourse + Communal Action creates the divine phenomena that must occur among Blacks.

Thanks for your post. I wonder if African Theology has anything to good to offer or anything to learn from. I look forward to hearing your thoughts on that.

Blessings,

Lou

I found this site to be very informative http://www.reformedblacksofamerica.org/blog1/index.php?itemid=300

Post a Comment