In God's gracious economy, the Lord sometimes gifts the body of Christ with people who can be expert tour guides to other faiths or other viewpoints. These men and women, sometimes by virtue of their studies, sometimes as a consequence of personal experience, are uniquely gifted to educate others regarding perspectives and beliefs different from our own. And that's a gift.

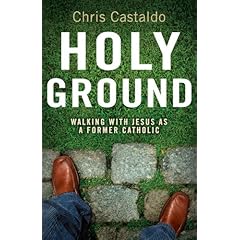

In God's gracious economy, the Lord sometimes gifts the body of Christ with people who can be expert tour guides to other faiths or other viewpoints. These men and women, sometimes by virtue of their studies, sometimes as a consequence of personal experience, are uniquely gifted to educate others regarding perspectives and beliefs different from our own. And that's a gift.Over the past couple weeks, I've had the opportunity to read Christ Castaldo's new book, Holy Ground: Walking with Jesus as a Former Roman Catholic. You can find Chris' website and some good video here.

Chris was raised on Long Island, New York, as a Roman Catholic and worked full-time in the Catholic Church for years. He is a graduate of Moody Bible Institute and Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, and he now serves as Pastor of Outreach and Church Planting at College Church in Wheaton.

In the book, Chris skillfully combines one part personal testimony, one part focus group research, one part theological study, and one hefty dose of pastoral discernment and care. In other words, what we have here is a well-informed, sensitive, winsome, and insightful look at Roman Catholicism from one who left Catholicism and now serves as an evangelical pastor at College Church in Wheaton, IL. It's a real tool in the hands of pastors and family members often called to love and understand those inside Roman Catholicism.

I had the privilege of asking Chris a question or two, and I hope you enjoy the exchange!

1.) How would reading Holy Ground specifically benefit pastors?

Here it is in a nutshell: estimates say there are 14 million former Catholics in the United States who now identify as “evangelical” or “born again.” These are people who struggle to understand how their Catholic background still exerts influence upon them and who need to confront patterns of faith that are less than biblical, while simultaneously applying more of the gospel. At the same time, they wrestle with the challenge of effectively communicating the hope of Christ to Catholic family and friends. Most of us pastors have at least some of these folk in our churches. Holy Ground is written to help church leaders offer these individuals the contextualized form of discipleship they so desperately need.

Through an extended narrative describing my personal journey as a devout Catholic who worked with bishops and priests before eventually becoming an Evangelical pastor, Holy Ground tries to help readers to understand:

- Priorities which drive Catholic faith and practice

- Where lines of continuity and discontinuity fall between Catholicism and Evangelicalism

- Delicate dynamics that make up our relationships

- Principles for lovingly sharing the gospel of salvation by faith alone

- Historical overview from the Reformation to the present

Because Holy Ground is a pastoral work, there are several aspects pertinent to church ministry, but let me mention one I constantly deal with in my role of equipping our people for evangelism.

When we communicate the gospel to Catholics we often make the mistake of thinking that our conversations should directly address doctrinal issues. This is not only incorrect, it is impossible. When speaking to a friend about faith, we don’t speak directly to his religious beliefs; we speak to a person who holds religious beliefs. This is a crucial, overlooked distinction. John Stackhouse in his book Humble Apologetics puts his finger on it:

To put it starkly, if “message without life” was sufficient, Christ didn’t need to perform signs, nor did he need to form personal relationships in which to teach the gospel to those who would believe him and spread the word. He could simply have hired scribes to write down his message and distribute it (John G. Stackhouse, Jr., Humble Apologetics: Defending the Faith Today. [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002], 134).

This is what sometimes frustrates me about books written to equip Evangelicals to discuss Jesus with Catholics. They seem to operate according to the assumption that if you can simply pile up enough proofs, Catholics will have no choice but to surrender under the weight of your argument. Sure, we must have reliable evidence and must know how to marshal it effectively; but, we can’t ignore the personal, cultural, historical, and religious dynamics which are also part of these conversations. Like: What are the different types of Catholics in America today? How do Catholics generally view Protestants? What are the prevailing caricatures? What landmines do we routinely step on? What language is helpful and what terms undermine fruitful discussion? How can we navigate through controversies related to one’s ethnic background or the history of anti-Catholicism in America? Where is common ground and where must we necessarily draw lines of distinction? And the list goes on. Holy Ground addresses these and other such questions in order to help ourselves and the people we serve more effectively proclaim Christ’s glory among our Catholic friends and loved ones.

2.) In light of the Decrees of Trent, wouldn’t we still have to say that official Catholic doctrine on the matter of justification rises to the level of error so serious that it amounts to ‘another gospel’ – thus warranting an apostolic anathema?

The most helpful book I’ve read on this topic has been Justification by Faith in Catholic-Protestant Dialogue: An Evangelical Assessment by Anthony Lane, Professor of Historical Theology at London School of Theology. Tony Lane is a fine scholar (it’s a T&T Clark book, so if you buy it, do so when you still have a sizable chunk in your book budget). Here are a couple of Professor Lane’s conclusions, which I agree with and have found helpful.

Is the positive exposition of the Tridentine decree compatible with a Protestant understanding?

“No. When the difference in terminology is taken into account and when allowance is made for complementary formulations the gap turns out to be considerably narrower than is often popularly supposed, but a gap there remains.”

Do the Tridentine canons condemn the Protestant doctrine or only parodies of it?

“Many of the canons do not directly touch a balanced Protestant understanding, but a number clearly do. The verdict of The Condemnations of the Reformation Era (a joint ecumenical commission which met in the early 80’s) is as much a statement about the intentions of the churches today as a statement about the intentions of Trent and the Lutheran confessions.”

According to Lane’s conclusion, disagreement between the Catholic and Protestant understanding of justification remains, although it may not be as profound as we tend to think. Still, giving the binding nature of Trent’s decrees, evangelical Protestants remain in the crosshairs of the Catholic Church’s anathematizing canons. To the extent that Catholics operate according to this Tridentine framework (i.e., defining their position over and against justification by faith alone), they appear to be skating on the same thin ice as Paul’s Galatian interlocutors and in imminent danger of falling into the frigid water of “another gospel.”

Yet, we must realize that many Catholics, including Pope Benedict himself, don’t understand justification in this Tridentine light. For instance, in the Pope’s sermon on justification in Saint Peter’s Square on November 19, 2008 he said, “Being just simply means being with Christ and in Christ. And this suffices. Further observances are no longer necessary. For this reason Luther’s phrase: ‘faith alone’ is true, if it is not opposed to faith in charity in love.” A week later on November 26 in the Paul VI Audience Hall the pontiff continued this emphasis, “Following Saint Paul, we have seen that man is unable to ‘justify’ himself with his own actions, but can only truly become ‘just’ before God because God confers his ‘justice’ upon him, uniting him to Christ his Son. And man obtains this union through faith. In this sense, Saint Paul tells us: not our deeds, but rather faith renders us ‘just.’”

Lest you think the Pope’s statements were an out of turn, momentary flash in the pan, you can also read them in his recent book Saint Paul (Pope Benedict XVI. Saint Paul. [San Francisco: Ignatius Press], 82-85). This same note is hit by many Catholic theologians, particularly those like Beckwith who identify as evangelical Catholic.

Of more immediate concern to me is the penetration of the biblical gospel—the message of divine grace accessed through faith alone—into the hearts of Catholic people who haven’t a clue why Jesus died, much less how salvation is appropriated. Catholic philosopher Peter Kreeft describes this problem:

“There are still many who do not know the data, the gospel. Most of my Catholic students at Boston College have never heard it. They do not even know how to get to heaven. When I ask them what they would say to God if they died tonight and God asked them why he should take them into heaven, nine out of ten do not even mention Jesus Christ. Most of them say they have been good or kind or sincere or did their best. So I seriously doubt God will undo the Reformation until he sees to it that Luther’s reminder of Paul’s gospel has been heard throughout the church” (Peter Kreeft. “Ecumenical Jihad.” Reclaiming The Great Tradition. Ed. James S. Cutsinger. [Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1997]. 27).

This is the concern of Holy Ground—that the grace of God in salvation remains central. When talking with Catholics, there are myriads of potential rabbit trails. We may enter into a conversation to talk about how Jesus provides life with meaning and suddenly find ourselves enmeshed in a debate about the apocrypha or Humanae Vitae. Sometimes it’s right to broach these subjects, but too often we do so at the expense of the gospel. This is tragic. What does it profit a person if he explicates a host of theological conundrums without focusing attention upon the death and resurrection of Jesus? In all of our discussion with Catholics we must consider, celebrate, and bear witness to the splendor and majesty of our Savior, the one who died, rose, and now lives.

3.) What are the distinct features of Holy Ground that separate it from other such books?

Among evangelical books that address Catholicism, Holy Ground has a couple of features that make it unique. First, many such books convey an unkind attitude. The doctrinal emphasis of these works is commendable, but the irritable tone rings hollow and fails to exhibit the loving character of Jesus. It's the tone that my seminary professor warned against when he said, "Don't preach and write as though you have just swallowed embalming fluid. As Christ imparts redemptive life, so should his followers." This life is communicated in the content of God's message and also in its manner of presentation. Therefore, I seek to express genuine courtesy toward Catholics, even in disagreement.

Second, most books on Roman Catholicism and Evangelicalism emphasize doctrinal tenets without exploring the practical dimensions of personal faith. Important as it is to understand doctrine, the reality is there's often a vast difference between the content of catechisms and the beliefs of folks who fill our pews. Holy Ground is concerned with understanding the common ideas and experiences of real-life people.

4.) What should be the centerpiece of Catholic/Protestant dialogue?

When talking with Catholics, there are myriads of potential rabbit trails. We may enter into a conversation to talk about how Jesus provides life with meaning and suddenly find ourselves enmeshed in a debate about the apocrypha or Humanae Vitae. Sometimes it’s right to broach these subjects; but too often we do so at the expense of the gospel. This is tragic. What does it profit a person if he explicates a host of theological conundrums without focusing attention upon the death and resurrection of Jesus? This, I would contend, is the “centerpiece”—considering, celebrating, and bearing witness to the splendor and majesty of our Savior, the one who died, rose, and now lives.

5.) How would you counsel Evangelical pastors and Christians in the care of persons leaving Roman Catholicism?

When folks leave the Catholic Church, more than anything, they are susceptible to the pendulum swing, the typical 180 degree turn that transforms mild fellows into Yosemite Sam-like Christians, ready to point and shoot any Roman Catholic that moves. This extreme, which is often justified in the name of “truth” or “biblical conviction,” is motivated more by frustration, anger, and a misunderstanding of duty: frustration with a Catholic background that perhaps confused the simple message of the gospel, anger with clergy who seemed to have mislead them, and a view of evangelism that regards aggressive opposition to Catholics as one’s duty.

Over and against this perspective, our people must view the circumstances and timing of their conversion in the light of God’s sovereignty. Instead of regret or anger, we can be thankful for the lessons that God has taught us through our Catholic experience and use these lessons to help others. Moreover, we would do well to remember Paul’s words in 1 Tim 1:5, “The goal of our instruction is love from a pure heart, good conscience and sincere faith.” Love is not antithetical to truth; it coalesces with it. Indeed, this is the best approach we can take toward Catholic friends and loved ones, speaking the truth in love.

The one other lesson I’d want to emphasize among those leaving the Catholic Church is the centrality of grace. Most former Catholics I’ve met (including myself) struggle with unhealthy religious guilt to such an extent that divine grace is difficult to accept. I devote an entire chapter to this in Holy Ground, but the bottom line is that we ex-Catholics benefit enormously from memorizing biblical texts dealing with grace alone such as Psalm 103:12, Rom 8:1, Gal 2:20, and 2 Cor 5:21. Eventually, God’s Word renews our minds to appreciate, both propositionally and existentially, that our right-standing with the Father has nothing to do with our meritorious behavior and everything to do with the once and for all victory of King Jesus, to whom belongs all the glory.

*********************************

Thank you, Chris, for this interview and for this wonderful book!

"Being just simply means being with Christ and in Christ. And this suffices. Further observances are no longer necessary. For this reason Luther’s phrase: ‘faith alone’ is true, if it is not opposed to faith in charity in love.”

ReplyDeleteShould statements like these affect evangelical-catholic cooperation? Their official catechism still states that water baptism is necessary for salvation to those able to ask for it and that merit is obtained through sacraments, etc. I do not understand how the Pope can make such statements without overturning past views (which he has not/cannot without changing the understanding of the infallibility of the church). So, then, what does he really mean by such a statement? How should evangelicals take it? Grateful for any illumination from those able to sift through all this.